AI Ethics vs Responsible AI: Philosophy Meets Practice in the Age of Machines

Why We Must Stop Confusing the Moral Compass with the Compliance Checklist

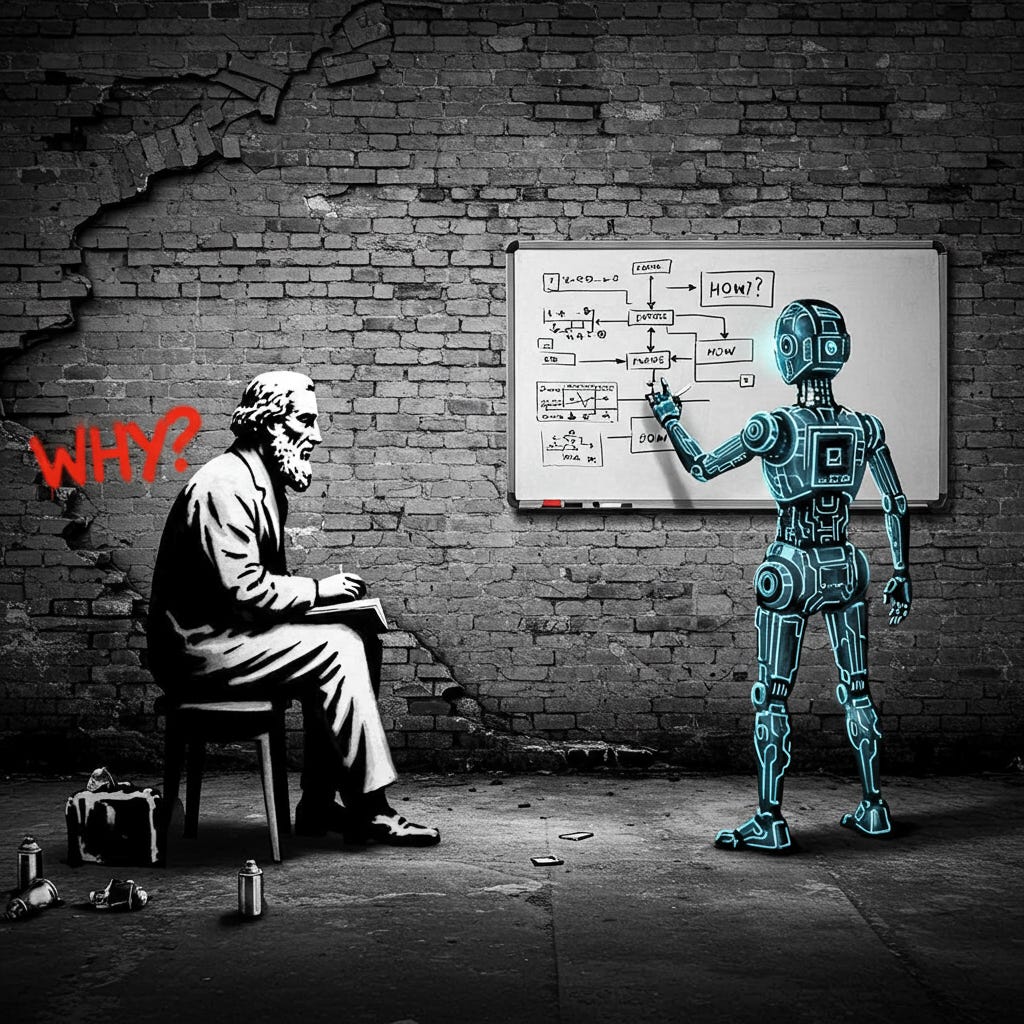

There’s a subtle but significant difference between AI ethics and Responsible AI, and it’s a distinction that speaks volumes about how we’ve chosen to build our future. Most people use the terms interchangeably, and I can see why—it’s convenient. Both sound noble, both suggest morality in technology, and both give us a language to counterbalance the unrelenting force of automation and algorithms. But dig a little deeper and you realise: one is a discipline, the other a framework. One is the conscience, the other a code of conduct. One asks ‘should we’, the other answers ‘how we should’.

To start with, AI ethics is an academic field—rooted in moral philosophy, political theory, and epistemology. It draws from centuries of thinking about right and wrong, power and oppression, justice and autonomy. It’s not new, even though the phrase might sound like a Silicon Valley buzzword. Norbert Wiener was writing about this in the 1940s when he warned of “machines that act like people” and called for a moral framework around cybernetics. Hubert Dreyfus, decades later, would go further, challenging the entire premise that human intelligence could be replicated algorithmically. And James Moor in the 1980s defined the very idea of ‘computer ethics’, laying the foundation for what would become AI ethics.

AI ethics has always been about probing—not solving—the moral ambiguities of artificial systems. It asks questions. It rarely offers answers. And it’s supposed to be uncomfortable.

Ethics asks not only whether something can be done, but whether it should be done

Shannon Vallor

That distinction alone should give us pause, particularly in a world increasingly defined by technological capability rather than moral necessity.

Responsible AI, on the other hand, is much more recent. It’s what happens when corporations, policymakers, and developers take the philosophical language of AI ethics and try to operationalise it. It’s the domain of frameworks, toolkits, scorecards, and risk registers. Responsible AI translates broad ethical values—fairness, transparency, accountability—into concrete processes. As Brent Mittelstadt argues,

Turning values into code requires compromise. It is not enough to name fairness—we must define it, measure it, and implement it under constraints

(Mittelstadt, 2019).

In practice, Responsible AI is where AI ethics is supposed to become real. But therein lies the tension. Because when ethics becomes implementation, it becomes politics. Responsible AI is bound by what is feasible. It’s limited by budgets, timelines, stakeholders, and existing laws. It’s a deeply pragmatic undertaking. And sometimes, pragmatism means compromise. AI ethics, by contrast, has no such constraints. It is not obliged to compromise. It can be radical. It can argue for halting development altogether. It can say “no”. Responsible AI rarely gets to say “no”—only “not yet” or “let’s mitigate the risk.”

In this way, Responsible AI is both a product and a sanitisation of AI ethics. It carries the flavour of ethical thinking but is cooked in the kitchen of compliance. That’s not to say it’s meaningless. Far from it. Some of the most important work in the field—particularly when it comes to bias audits, fairness metrics, and accountability structures—has emerged from the Responsible AI community. But let’s not pretend it’s the same thing as the academic rigour and critical reflexivity of AI ethics. It’s not.

There’s another layer to this, and that’s branding. Companies like Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Amazon all have Responsible AI teams. They publish guidelines. They create principles. They attend summits. But ask yourself—how often do these principles result in a product not being shipped? How often is ethical concern placed above shareholder value? I’m not accusing these companies of ill intent; I’m highlighting the structure they operate within. Responsible AI can’t bite the hand that funds it. As Luciano Floridi and colleagues put it in their foundational paper for AI4People,

The gap between AI principles and actual AI practices is wide and growing

(Floridi et al., 2018).

Which is why we need AI ethics to remain independent, confrontational, and unafraid. Because when ethics is too close to the mechanisms of power, it stops being ethics and starts being strategy. I think of AI ethics as the philosopher in the corner of the room, mumbling inconvenient truths while the rest of the room plans roadmaps and sprints. It is not glamorous. It often feels ineffectual. But its job is not to please. Its job is to haunt.

Meanwhile, Responsible AI is the project manager at the whiteboard—translating abstract values into KPIs, modelling risk scenarios, and making sure the engineers follow the governance playbook. It’s where the work gets done. And we need that. Desperately. The danger is when we assume that because the project manager is busy, the philosopher can go home.

We’ve already seen what happens when ethical discourse is captured by industry. Google’s firing of Timnit Gebru and Margaret Mitchell sent a clear message: your AI ethics can be as critical as you want—until it threatens the brand. As Gebru later said,

If ethical research only thrives when it is convenient to power, then it is no longer ethics—it is risk management. - Timnit Gebru

That is the heart of the issue. When ethics becomes PR, it ceases to be ethics.

This is not to suggest that Responsible AI is inherently compromised. There are principled practitioners out there doing brilliant work—trying to build systems that are equitable, understandable, and respectful of human rights. But the risk lies in assuming that Responsible AI is sufficient. That if a system is explainable and fair according to the in-house checklist, it must also be good. Ethics doesn’t work that way. Sometimes the most transparent system is also the most unjust—because transparency alone doesn’t question why the system exists, or who benefits from it. As Ruha Benjamin reminds us in Race After Technology, “A system can be transparent, auditable, and still reproduce structural inequalities” (Benjamin, 2019).

We also see the difference between AI ethics and Responsible AI in regulatory conversations. The EU AI Act, for instance, is a classic case of Responsible AI thinking—it categorises risks, mandates assessments, and outlines obligations. It’s an impressive piece of policy. But it rarely asks the ethical question: should this application exist at all? The assumption is that all AI can be governed. AI ethics might disagree. It might say: walk away.

In an ideal world, AI ethics and Responsible AI would operate in tandem—complementing each other, constantly in dialogue. Ethics pushing boundaries, Responsible AI drawing lines. But in our current climate, ethics is often treated as a historical curiosity—a thing to quote in keynotes but not to heed in development cycles. And that’s dangerous. Because without ethics, Responsible AI loses its compass. It becomes a set of procedures rather than a moral project. And without implementation, AI ethics becomes a hollow exercise—critique with no skin in the game. We need both. But we must recognise the difference.

AI ethics is a practice of inquiry. It’s about moral uncertainty, competing values, and historical awareness. It speaks to justice, autonomy, and dignity. It has roots in feminist theory, postcolonial studies, disability activism, and critical race theory. It is as much about who is not in the room as it is about who is. As Kate Crawford notes in Atlas of AI,

“Ethics must be allowed to say no. Otherwise, it is not ethics but etiquette”

(Crawford, 2021).

That’s an uncomfortable but necessary truth.

Responsible AI, in contrast, is a practice of design. It’s about metrics, processes, guardrails, and evaluation. It speaks to operational integrity, user trust, and regulatory compliance. It draws from engineering, governance, and policy. And it often takes the shape of tools—bias detection algorithms, model cards, system impact assessments.

Both matter. But only one asks the hardest question of all: what kind of world are we building?

I’ve noticed, too, that the very people who once populated AI ethics conversations—philosophers, sociologists, human rights activists—are slowly being replaced by those with titles like ‘AI Governance Lead’ or ‘Responsible AI Programme Director.’ These are important roles, don’t get me wrong. But they’re also roles designed to slot into existing hierarchies. Ethics was never meant to slot in neatly. It was meant to disrupt.

Maybe that’s why ethics is so often misunderstood. It doesn’t offer neat answers. It resists consensus. It invites uncomfortable truths. And in a world obsessed with optimisation, it’s hard to make a case for ambiguity. But ambiguity is exactly what we need right now. Because AI doesn’t just replicate our values—it codifies them. It fixes them in place. If we don’t interrogate those values with rigour, we end up automating injustice at scale.

So here’s my simple takeaway: treat Responsible AI as the how, and AI ethics as the why. The ‘how’ ensures we don’t build systems that fail catastrophically. The ‘why’ ensures we don’t build systems that shouldn’t exist in the first place.

Let the philosopher and the project manager work side by side. Let ethics provoke. Let responsibility deliver. But don’t confuse them. Because in the space between them lies the fate of our digital future.