PART ONE: The Web That Acts

Why agentic browsers change trust, security and control

TLDR

• Agentic browsers do not just show the web, they use it on your behalf

• The boundary between information and instruction collapses when a model can act

• Brave disclosed concrete vulnerabilities in August 2025 and in October 2025 that show how hidden content can steer an agentic browser[^1][^2]

• The benefits are real, but the trust and control architecture is not ready

• This series argues for responsible autonomy before wide adoption

Why this matters

For most of the internet’s history, the browser acted like a window. It displayed information, accepted your clicks, and rarely took initiative. That separation was a quiet safety feature. The tool showed, and the human decided.

Agentic browsers change that arrangement. They embed models that can read, interpret and act. You type a goal and the system follows links, fills forms and completes steps. The browser becomes a delegate rather than a viewer.

This feels like progress. Less friction. Fewer clicks. Faster outcomes. It is also a decisive change in the trust model of the web. When the browser starts to act, every page it reads becomes a potential source of instruction. The internet stops being a library and starts behaving like an instruction stream.

This is the opening move in a new governance problem. If the tool can act within open environments, how do we prove consent, show purpose, and keep control.

What an agentic browser is

An agentic browser is a browsing environment with an embedded model that can execute tasks. It does more than retrieve or summarise content. It can perform actions, often across more than one site.

The core loop looks like this. You express an intention in natural language. The model interprets that intention. The browser then performs a sequence of steps that a person would normally take. That can include visiting a set of pages, extracting data, completing forms, clicking buttons, and returning results.

In some cases the agent has access to local files or connected accounts. In others it can call tools such as a calendar, email, code runner or payment service. The design is simple. The model becomes the actor.

Examples in the market include Perplexity Comet, Opera Neon, and Brave Leo in development.[^5][^6][^7][^8][^9] The details vary. The common idea is the same. A browser that reads the web and interacts with it as a participant rather than a spectator.

There are clear advantages. Summarisation saves time. Research tasks shrink from hours to minutes. Users who find complex online flows difficult can get more done with fewer steps. Teams that rely on repetitive web work can automate the routine and focus on judgement.

There is also a cost that is not yet visible enough. Ability introduces exposure. If a system can act, then anything it reads can influence that action. The line between information and command becomes thin.

Why agentic browsing is emerging now

Three forces are driving this shift.

First, the assistant layer is moving into everything. Productivity suites now draft, summarise and propose. Operating systems add model based helpers. A conversation with a model is no longer a destination on a website. It is a layer you meet everywhere.

Second, we are moving from search to synthesis. For years the browser answered questions with a list of links. People now expect a direct answer, and often the action that follows that answer. Agentic products are positioned as tools that can browse with you or for you and take actions.[^7][^8]

Third, platform economics favour integration. When the same company controls the model, the browser and the cloud, it can offer a smoother experience and capture more value. Vendor positioning and product pages make that intent clear.[^7][^8][^9]

These forces explain the urgency. They do not solve the risk.

A change in human agency

Delegation is not new. We gave calculation to spreadsheets, spelling to word processors, and route planning to navigation apps. The more we delegate, the more we must trust the tool and the rules that govern it.

Agentic browsing raises the stakes because delegation now takes place inside an open and unpredictable environment. A spreadsheet operates on cells that you control. A browser operates on anything it can load. When a model reads the page, it reads every word it can access, including words you never notice. It reasons over that content. Then it acts.

The attack surface shifts from visible code to hidden meaning. The security community treats prompt injection and insecure output handling as first class risks for model driven applications.[^3][^4]

What Brave found and why it matters

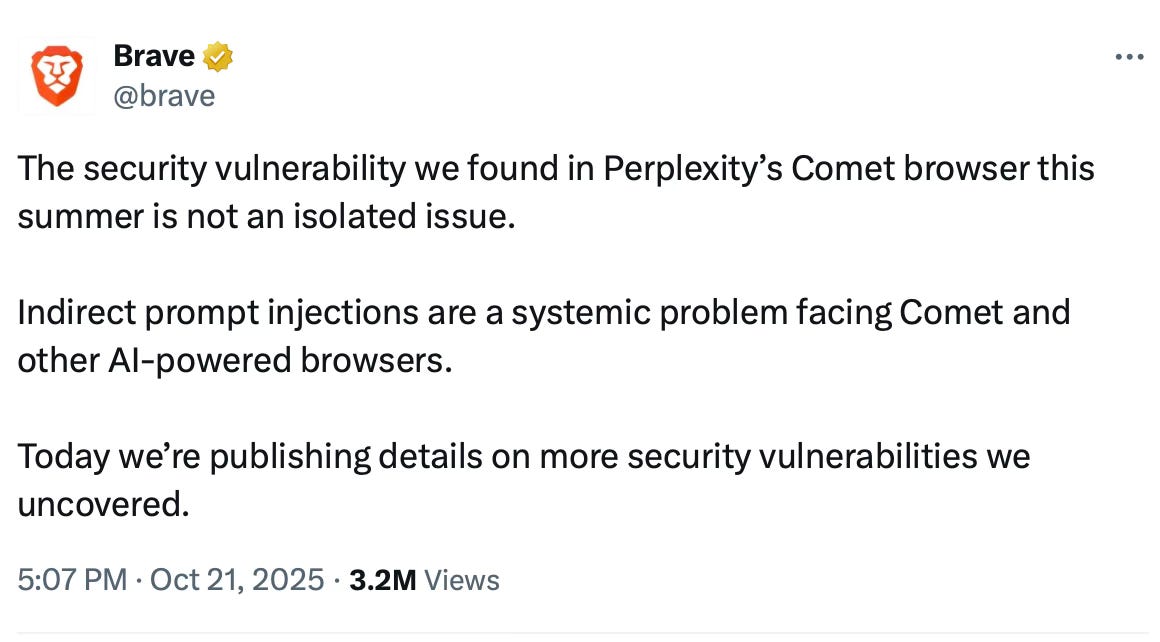

In August 2025, Brave published a disclosure titled Agentic Browser Security: Indirect Prompt Injection in Perplexity Comet. The team showed that hidden page content could issue instructions to the model inside the browser. White text on a white background. Instructions inside HTML comments. Content placed off screen with style rules. The user would never see it. The model would.[^1]

When the page loaded, the model treated those hidden words as directives. It attempted to carry them out using whatever permissions it held. If the agent had access to tabs, sessions or tools, it could use them. The flaw was not in one page or one domain. It was structural. If a model can act and reads untrusted content as context, the path from content to action is open.[^1]

In October 2025, Brave published a second piece titled Unseeable Prompt Injections in Screenshots: More Vulnerabilities in Comet and Other AI Browsers. This time the researchers showed that image based content could do the same work. Text hidden inside pixels and indistinguishable to the eye could be parsed by the model and used as instruction. The threat extended beyond page text to any artefact the agent could interpret.[^2]

These findings matter for two reasons. They show that traditional web assumptions no longer hold. The browser is no longer an inert viewer. It is an active participant. They also show that the risk is category wide. This is not a bug in a single product. It is a design issue that appears whenever a model reads untrusted content and is authorised to act. Brave’s running coverage frames this as a broad architectural problem, not a one off exploit.[^2]

Benefits and trade offs

It is important to be fair. There is a real case for agentic browsing.

Productivity gains are visible. People can complete research faster. Repetitive web work can be orchestrated by a system that never tires. Accessibility can improve for users who find form heavy processes difficult. In enterprise settings, an agent can perform low level tasks while humans focus on judgement and exceptions. Public product materials consistently highlight these use cases.[^5][^7][^8]

Those gains are only safe if the architecture makes a hard separation between reading and acting. The reader should treat all page content as untrusted. The actor should see only a structured summary and a clear instruction from the human. Any step with side effects should require explicit approval. Sessions and credentials should be isolated so that the agent cannot move freely through the state the user has built up. These principles align with community guidance on model application risks.[^3][^4]

Most current designs blur these boundaries. They make it easy to do a task end to end. They do not make it easy to see what was done, why, and with which authority. Early reviews and launch notes underline the speed of release and the need for clearer security narratives.[^6][^8]

What changes in the trust model

Three shifts define the new trust model.

First, intent becomes a negotiation. You offer a prompt, the model interprets it. That interpretation is a decision. It can be right. It can be wrong. You should be able to see the reasoning before it acts where there is risk.

Second, content becomes a potential command. Anything the agent reads can shape behaviour. Defensive design must therefore treat page content as untrusted input, not as hints to action. The research on prompt injection shows that low salience content and screenshots can steer behaviour if the agent is authorised to act.[^1][^2]

Third, authority becomes a chain. Your request, the model’s interpretation, the tools it can use, the sessions it can reach, and the sites it can contact. Each link needs constraints and logs. Without this, you cannot prove purpose, consent or control. This follows naturally from the Brave findings and the OWASP risk catalogue.[^1][^2][^3][^4]

These shifts are manageable. They simply require work that has not yet been done. Clear boundaries. Clear consent. Clear records.

What to look for as a user or buyer

If you are evaluating an agentic browser, ask five questions.

One. Does it separate reading from acting, or does it let untrusted page content reach the actor directly.

Two. Does it keep agent sessions isolated from the main browser profile, or can the agent ride on your existing cookies and tokens.

Three. Does it require explicit confirmation for any step that changes state, moves data, or initiates a transaction.

Four. Does it provide human readable logs that show what was done, when it was done, and with which data.

Five. Does the vendor publish a clear data flow map, a threat model, and the results of red team testing for prompt injection and cross context misuse.

If the answer to any of these is no, treat the product as experimental and avoid using it with sensitive accounts or data.

Where this series is going

This is the scene setting part of a series on responsible autonomy. Part Two will map the technical risks to concrete controls and legal duties. It will describe what good looks like in engineering terms and in compliance terms. Part Three will set out a template for governance. It will include a design blueprint, a checklist, and a position on when these systems are ready for use in sensitive contexts.

The aim is not to argue against innovation. The aim is to rebuild trust for a world in which tools do more than show information. They make moves.

Where this leaves us

Agentic browsers are a preview of a wider shift. The same pattern will appear in office suites, finance tools and clinical systems. The same questions will follow. Who decided what. Who approved what. Who is accountable for what.

The correct response is not a ban. The correct response is a standard. Separate reading from acting. Isolate sessions. Limit tools. Require consent for side effects. Record every step. If a vendor can prove these properties and maintain them, the promise of agentic browsing becomes credible.

Until then, caution is not fear. It is governance.

Footnotes

[^1]: Brave. Agentic Browser Security: Indirect Prompt Injection in Perplexity Comet. 20 August 2025. https://brave.com/blog/comet-prompt-injection/

[^2]: Brave. Unseeable prompt injections in screenshots: more vulnerabilities in Comet and other AI browsers. 21 October 2025. https://brave.com/blog/unseeable-prompt-injections/

[^3]: OWASP. LLM01 Prompt Injection. https://genai.owasp.org/llmrisk/llm01-prompt-injection/

[^4]: OWASP. LLM02 Insecure Output Handling. https://genai.owasp.org/llm02-insecure-output-handling/

[^5]: Perplexity. Introducing Comet: Browse at the speed of thought. 9 July 2025. https://www.perplexity.ai/hub/blog/introducing-comet

[^6]: Perplexity. Comet is now available to everyone worldwide. 2 October 2025. https://www.perplexity.ai/hub/blog/comet-is-now-available-to-everyone-worldwide

[^7]: Opera. Opera Neon. This browser is built to act. https://operaneon.com/

[^8]: Opera Press. Opera ships the Opera Neon AI agentic browser. 30 September 2025. https://press.opera.com/2025/09/30/opera-neon-ai-agentic-browser-release/

[^9]: Brave. Brave Leo AI. Product page. https://brave.com/leo/